Shaiboub William Arsal was convicted of murdering his cousin and another young Coptic Christian in El-Kosheh, a village in Upper Egypt. Then 38 years of age, he was sentenced to 15 years at hard labor, the maximum penalty allowed for manslaughter under Egyptian law.

But in fact, the illiterate day laborer had become the scapegoat in a flagrant cover-up of police brutality in Egypt's Sohag province.

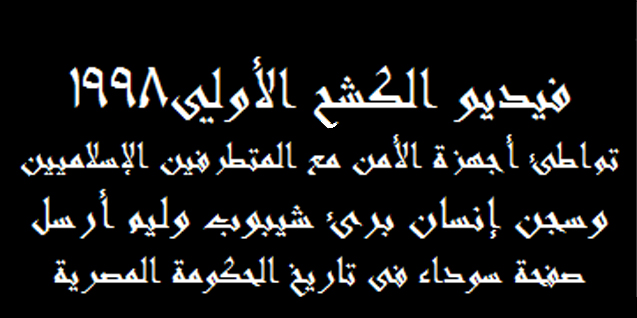

Arrested the morning after the double murder, Shaiboub was among more than 1,000 Christian villagers interrogated, threatened and abused over the next few weeks by local police investigating the crime. Rather than pursue the Muslim suspect named by the Coptic community, the police seemed determined to find one or more Christian culprits.

But when the local Coptic bishop publicly protested against their harsh treatment of his flock, police officials settled on Shaiboub as the guilty party. After holding two Coptic army conscripts under torture for several weeks, the police forced them to sign prepared statements that they had seen Shaiboub commit the murders.

The two Copts later retracted the confessions as false, declaring they were forced to sign them. But the Sohag Criminal Court refused their retractions, declaring they were "void of any credible evidence that the claims of coercion were true." Apart from police testimony, the two written statements were the prosecution's only evidence in the case.

Reacting to international inquiries on the case, the Egyptian government claimed the murders were a "normal criminal incident" that had been "grossly exaggerated" by the foreign press. A half-hearted inquiry into the alleged police excesses was quietly whitewashed by a judicial investigation, and after repeated delays and deferments, Shaiboub's guilty verdict was announced on June 5, 2000.

In contrast to Shaiboub's sentence, two self-confessed Muslim murderers who shot and killed a Coptic monk in September 1999 were given only seven-year prison terms.

By August 2000, defense lawyers had filed an appeal of the Sohag Criminal Court's verdict before the Court of Cassation, Egypt's highest court of appeal.

But to date, there has been no answer.

"The courts of Egypt are under no obligation to answer this appeal," Coptic lawyer Mamdouh Nakhla told Compass. Although the Court of Cassation normally responds to such an appeal application within six months to three years, the Egyptian legal system can choose to ignore it entirely.

"Or, they could just refuse it, say no, and it would be finished," Nakhla said. "That's just as likely," he admitted, noting that if Shaiboub's conviction should be overturned, the courts would then be obliged to resolve the case by finding the real culprit.

Shaiboub is currently incarcerated with some 1,500 other prisoners at a prison farm, part of the Tora maximum-security prison complex on the southeast edge of Cairo. His family, who live 330 miles away, can visit him once a month, for 30 minutes.

Although isolated in a solitary cell while under trial, Shaiboub now shares a cell with 25 or 30 other prisoners at a time, his lawyer said. Under current prison regulations, after serving three years of his hard-labor sentence, he would be eligible on the basis of good behavior for transfer to a general or light-security prison.